Our Seven–Their Five: A Fragment from the Story of Gung Ho is a fictional work by Rewi Alley, the technical director of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Alley wrote this story in 1943, while living in a village in the Qinling Mountains of Shaanxi Province. He had recently returned from Hunan, where he observed famine conditions and the devastating effects of the Japanese advance. Drawing on these experiences, he produced a vivid portrait of ordinary life in wartime China. However, the book was not published until 1963, well after the Communist victory, at a time when Chiang Kai-shek was portrayed as a central antagonist of the people’s struggle. Reflecting that political context, Alley depicts the Nationalist regime as obstructing the cooperative movement, a view consistent with 1960s ideological narratives.

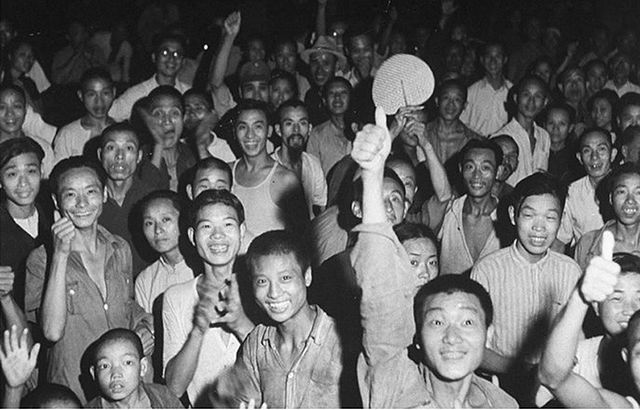

Our Seven–Their Five is not centered on one protagonist. Instead, the story follows a group of refugees from Hunan Province who flee famine and war to settle in a small town. There, they meet Fu, a cooperative organizer educated in Beijing, who helps them form a cooperative enterprise. According to the cooperative rules, at least seven people were needed to register a group, but the refugees were only five. They therefore joined forces with seven weavers to reach the required number—hence the title, “Our Seven–Their Five.” With support from the Cooperative Federation, providing loans and organizational guidance, they managed to launch a small but successful operation. Through teamwork and persistence, the refugees began to rebuild their lives.

The story stands out because it offers a rare ground-level view of wartime China. Rather than focusing on generals, political leaders, or major battles, Alley documents the daily realities of refugees, laborers, and peasants whose survival depended on cooperation. In his depiction, life and death coexist with unsettling normalcy: people die, yet work continues; tragedy is woven into the fabric of everyday endurance.

There is even humor. In one memorable scene, a foreign inspector visits a cooperative (clearly Alley himself), and local children gossip about how strange the foreigner looks, especially his long nose, which they imagine could dip right into his teacup. Moments like this humanize the story and reflect Alley’s lighthearted way of addressing cultural encounters.

Equally important is his refusal to reduce Chinese society to a simple Communist vs. Nationalist binary. Instead, Alley portrays a complex human landscape shaped by hardship, survival, and moral ambiguity. He writes with empathy for the refugees and displaced people, emphasizing their struggles to adapt to rural life amid famine, disease, and Japanese occupation.

The story also captures the class tensions and corruption that persisted even within the cooperative system. In one episode, we see a local landlord sponsoring a cooperative not out of solidarity but to gain easy access to credit and manipulate grain prices during a period of hyperinflation. Such moments reveal how some cooperatives, especially in Nationalist-controlled areas, were exploited as quasi-private enterprises rather than genuine collectives.

By highlighting these abuses, Alley underscores that the cooperative movement was not uniformly idealistic or successful. Some cooperatives functioned as large factories; others resembled small capitalist ventures; and still others truly fulfilled their mission of mutual aid and community resilience. Amid this uneven landscape, Alley still finds hope in the cooperative spirit and endurance of ordinary Chinese people.