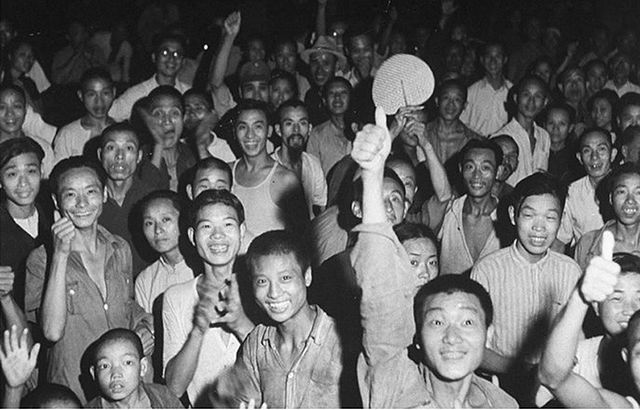

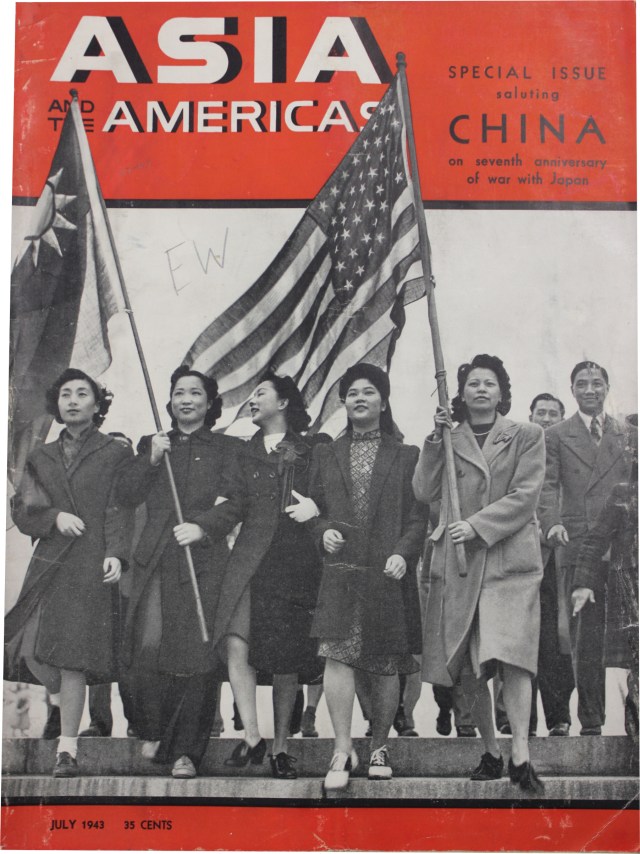

One of the major accomplishments of Indusco (the American Committee in Aid of Chinese Industrial Cooperatives) was its international propaganda and fundraising campaign. In addition to publishing the monthly Indusco Bulletin in English to inform foreign supporters about cooperative activities, the Hong Kong-based International Committee for Chinese Industrial Cooperatives produced pamphlets, sent speakers abroad to advocate for China’s wartime cause, and organized fundraising events to support relief efforts. Indusco headquarters also published Chinese-language periodicals and pamphlets that featured workers’ and peasants’ testimonies to mobilize domestic support. While much of this propaganda relied on text, visual materials, such as photographs, drawings, and maps, played a crucial role in communicating the movement’s message.

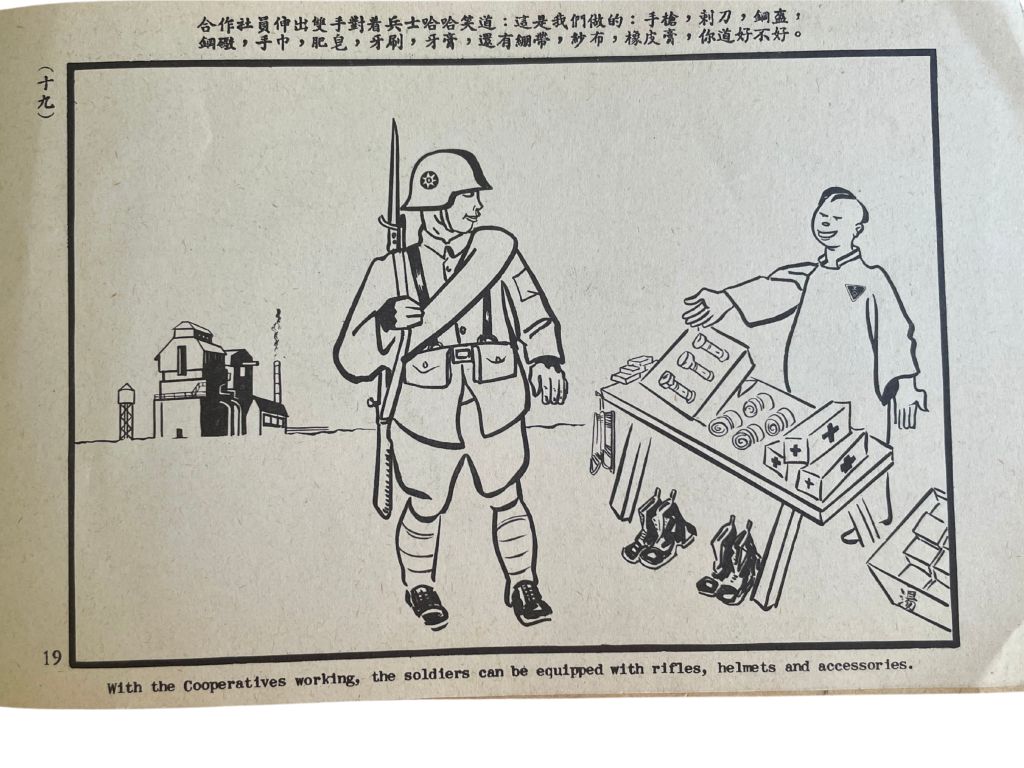

Among these visual materials, Jack Chen’s bilingual pamphlet stood out for its compelling depiction of the goals and accomplishments of the cooperative movement. The booklet, which included twenty original drawings illustrating the importance of industrial cooperatives during the war, was used not only for propaganda but also as a key fundraising tool, promoted widely through the Indusco Bulletin.

Jack Chen (1908–1995) was one of the leading cartoonists in wartime China. Trained in art in Soviet Russia, he became a major advocate of socialist realism in Chinese art during the 1930s. Born in Trinidad to a biracial family, Chen used his status as a British citizen in China to bypass local censorship. He published widely in both Chinese and international media, organized exhibitions to foster exchange between Chinese and foreign artists, and supported China’s resistance through his artwork.

A communist sympathizer, Chen visited the Communist base in Yan’an in 1938 and wrote about the experience in the January 1939 issue of Asia magazine. He is perhaps best known for his later books, A Year in Upper Felicity: Life in a Chinese Village During the Cultural Revolution, The Sinkiang (Xinjiang) Story, and The Chinese of America. His personal papers are held at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives in California. For a detailed study of his impact on the Chinese art world, see Paul Bevan’s A Modern Miscellany: Shanghai Cartoon Artists, Shao Xunmei’s Circle, and the Travels of Jack Chen, 1926–1938.