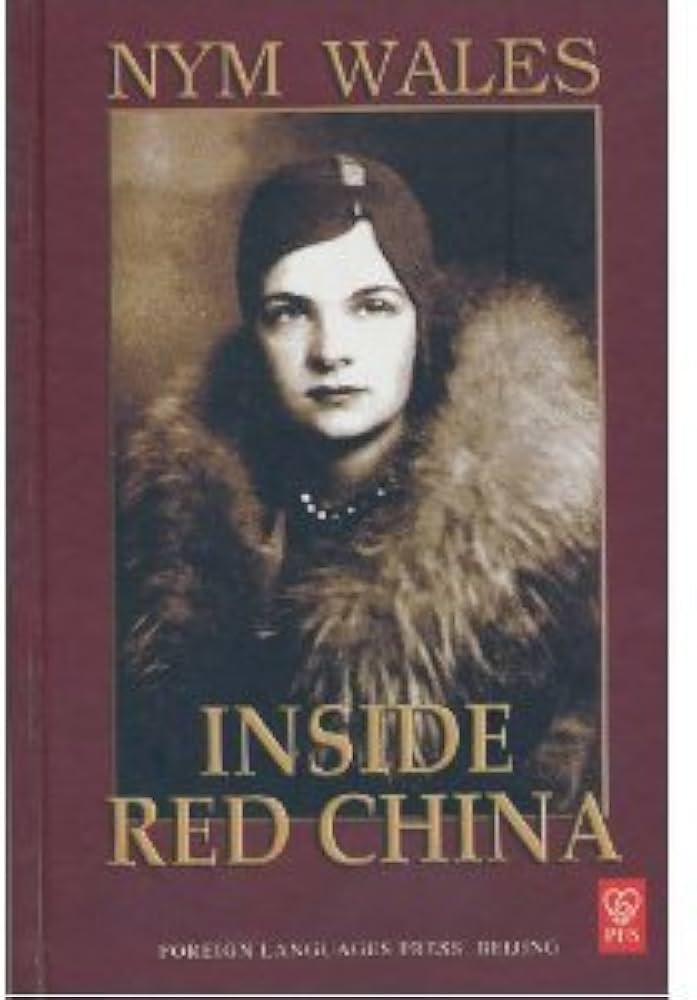

During the 1930s, Helen Snow lived the glomorous and dangerous life of a journalist in China, eventually publishing seven books on the Communist accession with her husband Edgar. Inside Red China is her firsthand account of the cataclymic events from May to September, 1937 in the Soviet capital Yenan just before the Red Army joined Chiang Kai-shek to defeat the Japanese.

Building a Nation at War argues that the Chinese Nationalist government’s retreat inland during the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), its consequent need for inland resources, and its participation in new scientific and technical relationships with the United States led to fundamental changes in how the Nationalists engaged with science and technology as tools to promote development.

Ida Pruitt (1888-1985), born of American missionaries and raised in a rural Chinese village at the end of the nineteenth century, witnessed almost a century of China’s revolutionary upheavals. She was the first Director of Social Service at Peking Union Medical College, where she established social casework in China, and later served as the executive secretary of the American Committee in Support of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, the only U.S. aid agency to support both Nationalist and Communist regions during the Chinese Civil War. She was also one of the early advocates for U.S. diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China. Marjorie King tells the story of this remarkable woman and brings a unique perspective to the study of modern Chinese history.

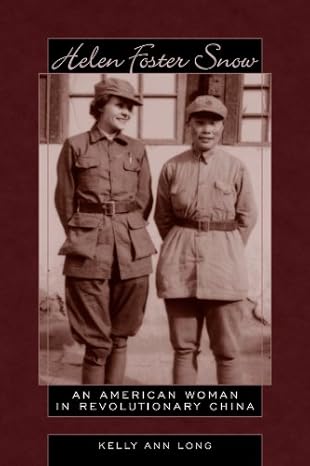

Helen Foster Snow: An American Woman in Revolutionary China tells the story of a remarkable woman born in rural Utah in 1907, who lived in China during the 1930’s and became an important author, a lifelong humanitarian, and a bridge-builder between the United States and China.

As Kelly Ann Long recounts in this engaging biography, Helen Foster Snow immersed herself in the social and political currents of a nation in turmoil. After marrying renowned journalist Edgar Snow, she developed her own writing talents and offered an important perspective on emerging events in China as that nation was wracked by Japanese invasion, the outbreak of World War II, and a continuing civil war. She supported the December Ninth Movement of 1935, broke boundaries to enter communist Yenan in 1937, and helped initiate the “gung ho” Chinese Industrial Cooperative movement.

A study of the Chinese Communist Party’s revolutionary enterprise in northern Shaanxi during the 1934-45 period, this book argues that the “Yan’an Way,” long celebrated by the Party as the foundation and model for its success, was a product of quite special circumstances that were not replicable in most other parts of China.

Agnes Smedley, author of Daughter of Earth, worked in and wrote about China from 1928 to 1941. These 18 piecesall out of print and most unavailable even in public librariesare based on interviews with revolutionary women. They include descriptions of the massacre of feminists in the Canton commune, of the silk workers of Canton whose solidarity earns them the charge of lesbianism, and of Mother Tsai, a 60-year-old peasant who leads village women in smashing an opium den.

In this brand new radical analysis of globalization, Cynthia Enloe examines recent events―Bangladeshi garment factory deaths, domestic workers in the Persian Gulf, Chinese global tourists, and the UN gender politics of guns―to reveal the crucial role of women in international politics today.

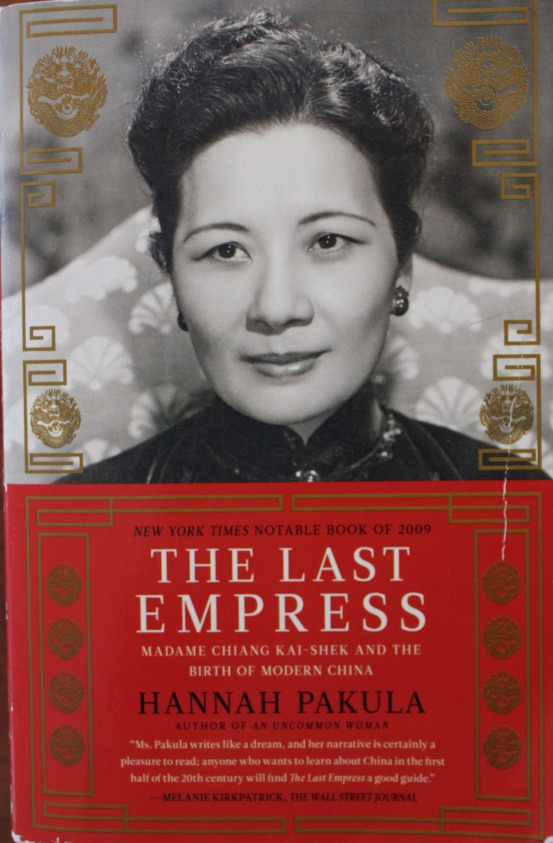

With the beautiful, powerful, and sexy Madame Chiang Kai-Shek at the center of one of the great dramas of the twentieth century, this is the story of the founding of modern China, starting with a revolution that swept away more than 2,000 years of monarchy, followed by World War II, and ending in eventual loss to the Communists and exile in Taipei. Praised by China scholar Jonathan Spence for “an impressive amount of telling material, drawn from a wide array of sources,” Pakula presents an epic historical tapestry, a wonderfully wrought narrative that brings to life what Americans should know about China—the superpower we are inextricably linked with.

Spanning the century from the Taiping Rebellion through the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, this is the first comprehensive history of women in modern China. Its scope is broad, encompassing political, economic, military, and cultural history, and drawing upon Chinese and Japanese sources untapped by Western scholars. The book presents new information on a wide range of topics: the impact of Western ideas on women, especially in education; the importance of women in the labor force; the relative independence enjoyed by some women textile workers; the struggle against footbinding; the influence of anarchism; the participation of a women’s

Presents a comprehensive survey of the two-hundred-year relationship between the United States and East Asia

Across the Pacific (first published 1967) spans nearly two centuries of evolving diplomatic, cultural, and intellectual interactions among the United States, Japan, and China. It doesn’t merely chronicle treaties and conflicts; instead, it delves into the “inner history”—the mental frameworks, cultural perceptions, and reciprocal understandings that influenced policymaking and international relations.

This book demonstrates how two goals – the substitution of socialist views for embedded traditional values, and the use of China’s actual and potential economic surpluses – have together formed the features of China’s economic development.

Studies of collaboration have changed how the history of World War II in Europe is written, but for China and Japan this aspect of wartime conduct has remained largely unacknowledged. In a bold new work, Timothy Brook breaks the silence surrounding the sensitive topic of wartime collaboration between the Chinese and their Japanese occupiers.

Rana Mitter focuses his gripping narrative on three towering leaders: Chiang Kai-shek, the politically gifted but tragically flawed head of China’s Nationalist government; Mao Zedong, the Communists’ fiery ideological stalwart, seen here at the beginning of his epochal career; and the lesser-known Wang Jingwei, who collaborated with the Japanese to form a puppet state in occupied China. Drawing on Chinese archives that have only been unsealed in the past ten years, he brings to vivid new life such characters as Chiang’s American chief of staff, the unforgettable “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, and such horrific events as the Rape of Nanking and the bombing of China’s wartime capital, Chongqing. Throughout, Forgotten Ally shows how the Chinese people played an essential role in the wider war effort, at great political and personal sacrifice.

This book, first published in 1974, was the only one to treat China’s foreign policy in its entirety, both as the subject of historically documented narrative (before and since the Liberation of 1949) and as the product of ideas themselves requiring analysis. It is also unique in approaching these ideas by the route they took into the Chinese for Mao the young Chinese republic was a ‘semi-colony’ over which the imperialists were falling out. His revolution would float like a boat on top of their ‘contradictions’.

In Revolutionary Nativism Maggie Clinton traces the history and cultural politics of fascist organizations that operated under the umbrella of the Chinese Nationalist Party (GMD) during the 1920s and 1930s. Clinton argues that fascism was not imported to China from Europe or Japan; rather it emerged from the charged social conditions that prevailed in the country’s southern and coastal regions during the interwar period. These fascist groups were led by young militants who believed that reviving China’s Confucian “national spirit” could foster the discipline and social cohesion necessary to defend China against imperialism and Communism and to develop formidable industrial and military capacities, thereby securing national strength in a competitive international arena. Fascists within the GMD deployed modernist aesthetics in their literature and art while justifying their anti-Communist violence with nativist discourse. Showing how the GMD’s fascist factions popularized a virulently nationalist rhetoric that linked Confucianism with a specific path of industrial development, Clinton sheds new light on the complex dynamics of Chinese nationalism and modernity.

Soong Mayling and Wartime China, 1937-1945: Deploying Words as Weapons focuses on the First Lady of China’s timely and critical contributions in the areas of war, women’s work, and diplomacy during China’s War of Resistance as inflected through gender. This book explores Soong Mayling through her own words by examining her speeches, essays, letters, telegrams, and news reports during the war period. How did Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s gender identity shape her interactions with other Chinese women, the male military and political leadership in the Republic of China, and the broader global public? How did Confucianism’s cardinal virtues and Chinese Christianity converge in Soong Mayling’s work and worldview? What were her main contributions as Secretary-General of the Chinese Air Force? Drawing on Chinese archival materials such as Chiang Kai-shek’s diaries and other records around the world, Esther Hu provides a historically informed perspective of the First Lady’s legacy within the context of World War II history, international cultural and military affairs, and transnational geopolitics.

This is the first history of the U.S. Army Air Corps unit that incorporated Gen. Claire Chennault’s famous “Flying Tigers.” During the dark days immediately after Pearl Harbor, most news from the Asian front was bad—with the exception of reports about the Flying Tigers and their successors, the 23rd Fighter Group. Day after day in the deadly skies over China, the 23rd’s shark-mouthed P-40s outfought the Japanese. No single American fighter group in World War II performed more varied missions, was more successful, or was more central to the war effort in its theater of operations. By the end of the war, the 23rd had tallied nearly six hundred aerial victories and destroyed nearly four hundred more Japanese aircraft on the ground. Carl Molesworth’s Sharks Over China is based on his interviews with the group’s survivors and contains numerous rare photographs.

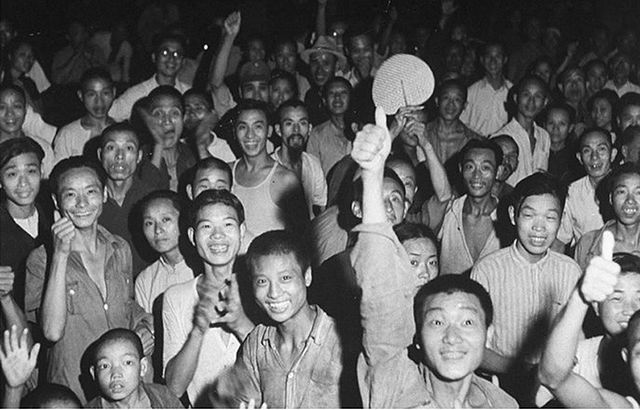

China’s resistance to Imperial Japan was the other great internationalist cause of the ‘red 1930s’, along with the Spanish Civil War. These desperate and bloody struggles were personified in the lives of Norman Bethune and others who volunteered in both conflicts. The story of Red Friends starts in the 1920s when, encouraged by the newly formed Communist International, Chinese nationalists and leftists united to fight warlords and foreign domination.

John Sexton has unearthearthed the histories of foreigners who joined the Chinese revolution. He follows Comintern militants, journalists, spies, adventurers, Trotskyists, and mission kids whose involvement helped, and sometimes hindered, China’s revolutionaries. Most were internationalists who, while strongly identifying with China’s struggle, saw it as just one theatre in a world revolution. The present rulers in Beijing, however, buoyed by China’s powerhouse economy, commemorate them as ‘foreign friends’ who aided China’s ‘peaceful rise’ to great power status.

A contemporary professional review describes the book as a “journalistic, political, and social autobiography.” It highlights Snow’s journey from his role in Shanghai to his ideological development in China, India, Russia, and beyond, interweaving personal anecdotes and political insights. The review also praises Snow’s informal reporting style and his candid reflections on mid-20th-century geopolitics

Liang Chin‑tung has written the most sophisticated version to date of Chiang Kai‑shek’s familiar analysis of America’s role in China during World War II, with special focus on the conflict between Chiang and Stilwell. Utilizing materials from Chiang’s files to which no other scholar has had access.

For most of its history, the People’s Republic of China limited public discussion of the war against Japan. It was an experience of victimization―and one that saw Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek fighting for the same goals. But now, as China grows more powerful, the meaning of the war is changing. Rana Mitter argues that China’s reassessment of the World War II years is central to its newfound confidence abroad and to mounting nationalism at home.

China’s Good War begins with the academics who shepherded the once-taboo subject into wider discourse. Encouraged by reforms under Deng Xiaoping, they researched the Guomindang war effort, collaboration with the Japanese, and China’s role in forming the post-1945 global order. But interest in the war would not stay confined to scholarly journals. Today public sites of memory―including museums, movies and television shows, street art, popular writing, and social media―define the war as a founding myth for an ascendant China. Wartime China emerges as victor rather than victim.

The shifting story has nurtured a number of new views. One rehabilitates Chiang Kai-shek’s war efforts, minimizing the bloody conflicts between him and Mao and aiming to heal the wounds of the Cultural Revolution. Another narrative positions Beijing as creator and protector of the international order that emerged from the war―an order, China argues, under threat today largely from the United States. China’s radical reassessment of its collective memory of the war has created a new foundation for a people destined to shape the world.

China Reporting is an oral history showing how the China correspondent of the 1930s and 1940s constructed his or her news reality or the network of facts from which their stories were written. How these men and women pooled information and decided upon the legitimacy of particular sources is explored. The influences of competition, language facility (or lack thereof), common personal backgrounds, camaraderie, and changes in American official China policy are also discussed, with special attention paid to the prescriptive, gatekeeping role of editors back home. This is an approach which has often been applied to the domestic journalist. China Reporting is a pioneering effort at using historical perspective to view the foreign correspondent in terms fo the total epistemological context in which he or she operates to produce the news that in turn provides the data base upon which the public and policy makers inevitably draw.